‘Doing Strategy’ as a Product Designer

There’s a scene in the first Matrix film where a newly freed Neo progresses through his training, gains confidence, and even one-ups his mentor Morpheus in a sparring contest. Seeing how Neo is ready for the next level, Morpheus leaps a giant gap from rooftop to rooftop and invites Neo to follow him.

Flush with confidence from his past successes, Neo convinces himself that he can make the same leap and attempts to follow his mentor.

Only to fall flat on his face.

This was my first experience as a principal product designer.

When I was first promoted beyond Senior Product Designer, I was glad to work at a higher level and help steer larger company initiatives. As part of this transition, doing “strategy” was added to my job description. I was already a master of my craft, but that was no longer enough on its own.

Fair enough, I can learn a new skill.

Only problem is I didn’t know what strategy was.

I started reading books, saving articles, shadowing product managers, and seeking out mentors. It felt like I was learning, but I still couldn’t hold my own in strategic conversations. I didn’t know how to apply what I’d learned.

It took me a long time to learn what “thinking strategically” looked like in practice. In hindsight, it held me back for several years earlier in my career.

This is the guide I wish I had when I was younger.

What Strategy Isn’t

Let’s start with what strategy isn’t. It sounds weird, but strategy is not about becoming a better designer. It’s not about:

- designing the best user experience.

- making it easier.

- setting metric goals.

- expanding one’s skillset into other creative areas.

- working on larger or more complex design projects.

- writing long docs and attending more meetings.

Basically strategy is not about design craft. Strategy is thinking beyond the pixels and the people using our products.

This was quite unnerving for me at the time. What’s the saying? “What go you here won’t get you there.”

As designers, we often get lost in our craft and forget the bigger picture. We love the creativity, research, and rush of making. But design can't exist without business.

— Mia Blume (@mialoira) April 11, 2023

So if strategy isn’t about design, what is it about?

What Strategy Is

In general, business strategy explains how a company tries to beat the competition.

It’s about not only understanding your users, but also the business and market, and using all three to define product goals and build the right things at the right time. It’s being able to think of many solid, profitable ideas for products. It’s looking at other products and being able to sense if they’ll be successful (with a degree of confidence).

Examples of thinking strategically include:

- Choosing what to do and what not to do

- Knowing what makes your company different

- Knowing how a company makes and loses money

- Balancing the user experience with business needs

- Being aware of risks in the ecosystem

- Knowing the company’s vision and connecting every project to it

- Knowing the delta between where we are today and where we want to be

Ideally every decision is aligned with a business strategy, even design decisions. So having a basic understanding of the company strategy is important.

What it looks like in practice

Well Ted, that all sounds well and fine, but what I do actually do??

This was the most frustrating part for me. Everything I read was so vague and hand-wavy. Things that sound great in print, but left me wondering what I can actually do to improve my strategy skills.

Looking back, here are the main areas that helped me think more strategically:

Understand the problem domain

Understanding a problem well means also understanding your competition, and understanding the systems around which this problem exists. - Julie Zhuo

We should be following industry news and know what our competitors are doing. Reading their press releases, following chatter on social, using their products, etc. I recently started reading online reviews of our competitors to learn what their customers love and don’t love about them.

Another way to learn about the domain is to speak with customers, especially about issues that have been outstanding for a while.

I have a standing list to questions to ask customers, so I’m ready even if I don’t have a specific project or feature to ask about:

- What were you using before our product? Why did you leave them and join us? If you’ve been with us for a while, what makes you stay? (Know their motivation)

- What works for you about Existing_Solution_Y? What is surprisingly easy to do? What is surprisingly hard? (Check table stakes)

- What’s the worst part about trying to solve Problem_X? How much does this suck? (Probe for pain)

- What’s the best experience you’ve ever had in solving Problem_X? (Determine the bar)

- If you had a magic wand, what would you use it on? (Gather potential visions)

We should find opportunities to talk directly with customers to find out what their problems really are. The real problem often gets lost in translation.

We should know the problem domain well enough to contribute to our product roadmaps, by both pitching ideas and helping prioritize projects. We should overlap a bit with our PMs here.

“At its core, all business is about making bets on human behavior.” — The Power of ‘Thick’ Data, WSJ

Fully understanding our product area and its business metrics is one of the best ways designers can position themselves as experts. When we’re in tune with the industry and our own customers, we can anticipate user and market needs and build something that people will want to pay for.

Understand the business

We should be paying attention at the company all-hands. It impacts our work. We shouldn’t wait for someone else to explain it to us. We should be asking our teams about the company’s goals, actively drawing a connection to our own work, and prioritizing projects with the strongest connections (more on this in a bit).

We should also learn all the ways the company makes (and loses) money. I found it helpful to make friends with folks in other departments.

- What makes folks buy or not buy from us? (Sales)

- What makes customers stay or churn? (Customer Success)

- How do we talk about ourselves publicly and to whom? (Marketing)

Product Managers know a little bit about all this and are great resource.

User experience is not just how somebody uses a product but also how they pay, maintain, upgrade, and dispose of a product. - Alen Faljic

Learning the business vision usually takes time, especially a larger companies, so this can be a slow burn.

Define what success looks like

Before building something new, it’s important to describe the desired outcome. If there are multiple goals, how do they trade off against each other? How do the goals contribute to the business? This is another area where we should overlap with our PMs.

How will we know we’ve won?

As designers, we sometimes leave this to others and jump straight into requirements and design activities. But it’s important to be an active voice in defining success metrics and what needs to be done to measure them.

Ruthlessly prioritize

Once we’ve learned what drives our customers and the business, we’ll have a better idea of how we should be spending our time. We’ll be able to plot each project that comes our way on an Impact vs. Effort matrix with some degree of confidence.

Our time, energy, and attention are not free, we so need to be strategic about how we spend them. Knowing how to prioritize lets us move faster on what matters most.

Hone storytelling and sales skills

Sorry designers, our work doesn’t sell itself. We need to show why our designs are critical to the company’s mission and directly solve problems worth solving.

To this end, it helps to learn how to “speak shark.” Yes, like the TV Show. While its antics are entertaining, the show also demonstrates how business acumen and product savviness help to sell an idea.

Sharks grill the “guppies,” asking them detailed questions about how they’ll take their products to market, how they’ll make money, what their sales projections will be, and so on. […] The more knowledgeable and business-smart an entrepreneur is, the better they do under questioning.

It’s helpful to be familiar with the people with the most influence over our product and business. They usually have a different vocabulary than designers. The more we learn this language, the more successful we’ll be selling our work and getting it into the product.

Change what you consume

We all keep up with design industry news. You’re doing it right now by reading this article. For many of us, it involves following our peers on social networks, listening to podcasts, reading books and articles, watching YouTube, attending classes or conferences, and subscribing to newsletters. We gradually become a better designers by absorbing this stuff over time.

The same works for learning concepts like business and product strategy, we just need to change what we consume.

Here’s a short, non-exhaustive list of resources I’ve found helpful in my own journey:

- 7 Things Every Designer Should Know About Business: It might sound like a click-bait-y article, but trust me it’s not. (Article)

- d.MBA guides (Website)

- 🐦 Podcasts for designers wanting to feel more comfortable discussing "strategy"?: Some great suggestions in the comments. (Twitter)

- Finding and Fostering Great Product Sense: On generating profitable ideas and making informed judgments. (Article)

- Selling to the VP of No: Honing those sales skills. (Book)

- Stratechery: Deep dives and analysis of the strategy and business side of technology. (Website)

- The Daily Upside): Daily newsletter with important and engaging stories in business. (Newsletter)

Bonus

At the 1:21:00 mark Figma Config 2023 opening keynote, Netflix’s Steve Johnson gave an excellent lightening talk titled “Design Without Business is Decoration.” A few tidbits of his advice:

- Design for business opportunities, not engineering constraints. Remember our job is to create value, not make our engineers’ lives easy.

- Understand your earning report and financial goals. Understanding what the company thinks is important helps us prioritize our projects (see “Ruthlessly prioritize” above).

- Know who’s on your board and what they value. Be familiar with the people influence our CEO and what they value. I’d never heard this before and think it’s brilliant!

- Know your competitor’s business goals. So we know what they value and know where we can intercept, bypass, or ignore them (see “Understand the problem domain” above).

- Be accountable for design goals which enable business outcomes. This wraps up everything: Make sure what we’re working on impacts the business in a meaningful way.

A Few Examples

Maybe it would help if we looked what this looks like in practice.

An example of good business strategy is how Microsoft Teams outperformed Slack. MS Teams leaned into its integration with other Microsoft products, strong sales and marketing resources, and established presence in the enterprise market. Even though Slack came first, has a more user-friendly interface, and a vibrant community and developer ecosystem, MS Teams is beating them in the market because of a good strategy. Microsoft realized that a “good enough” design was enough to win. Good UX isn’t enough on its own.

An example of bad company strategy is InVision’s failure to adapt to the changing market. The design software market is easy to enter and pretty competitive. InVision started as a prototyping tool to be used with Sketch, but they never became a holistic ecosystem for designers like Sketch and Figma. Their lack of focus further put them behind (anyone remember InVision Studio or Craft?). InVision’s didn’t realize what their competition was doing, and when they did they couldn’t execute fast enough to prevent their downfall.

What it looked like for me

I mentioned how early on I had trouble applying what I’d learned about business and strategy. I made a pretty big fool of myself on more than one occasion.

At a company meetup years ago, we had a 45min brainstorm about new product ideas. About 30 designers and product managers had a lively discussion. I was supposed to be one of the more senior people in the room, but I don’t remember saying anything the whole time. I couldn’t keep up. I don’t know if anyone else noticed, but I felt like a complete fraud.

So I kept trying, until eventually something clicked.

I could zoom out and see beyond the pixels and requirements. I was able to hold my own in a strategy conversation with my PM. I could determine a project’s impact and time-box accordingly. I started thinking of features as “things we could package and sell” rather than simply “stuff we add to a product.” I brainstormed new product ideas by looking at other industries.

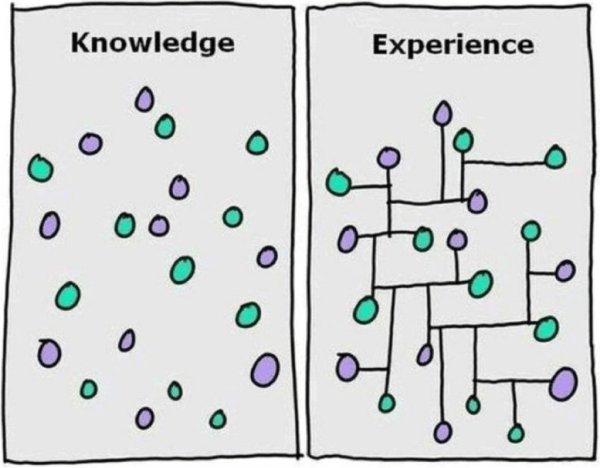

I don’t know that I had an “a ha!” moment, but I started connecting the dots. Slowly but surely.

It took me a couple years of trying and failing to finally get the hang of it. Practice makes perfect, I suppose.

Conclusion

Design leaders need more than just design skills. Understanding business and strategy is one the most impactful things designers can learn to lead teams and attain meaningful results.

This is especially in the age of Ai.

Creative teams that are solely focused on quality and craft as their outcome are going to find themselves fighting a losing battle.

With Ai eating away at the maker aspects of our job, now is a good time to lean into the product and business aspects of being a product designer. Strengthening our skills in these areas increases our ability to contribute to our company’s overall success, and future-proof’s our career stability in the process.

Some say it’s good to end with a quote. He says someone else has already said it best. So if you can’t top it, steal from them and go out strong. So here’s one from my buddy Neil:

Thanks to Marshal, Palko, Silvi, and Lau for reading early versions of this article.